Thomas Edison pours whole houses from concrete

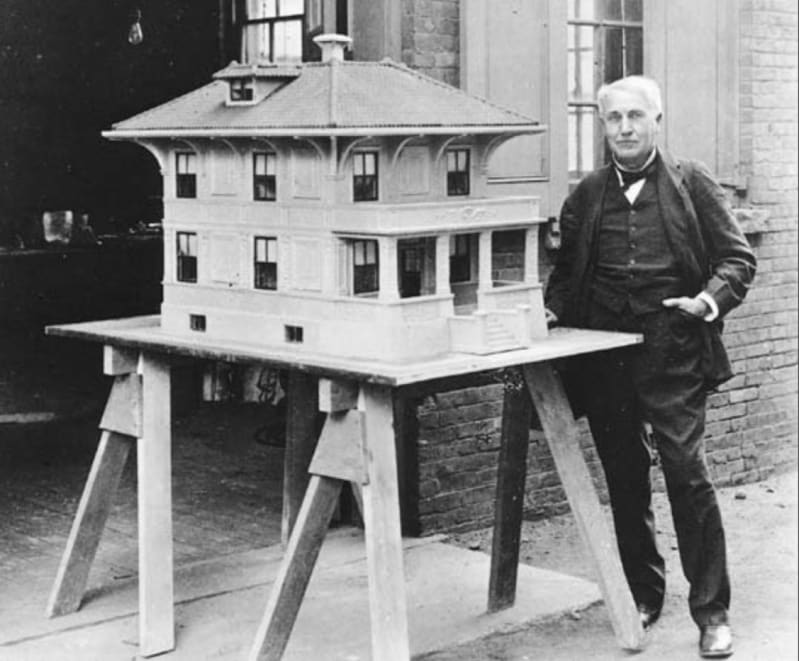

Historians of construction focus on Europe as the place where houses built of concrete were pioneered at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. But over in West Orange, New Jersey, Thomas Edison was dreaming in his laboratory of an entire concrete house made in a single operation, including not just walls and floors, but the foundations, the roof, the staircase, chimneys, mantelpieces, even ceiling decorations. It would be like casting a large and complex sculpture. The photo shows the inventor with a model.

In 1899 Edison had set up a plant making Portland cement – one of the ingredients of concrete, together with sand and gravel – which was losing money. He hoped to create a new market for its product by mass-producing cheap houses, that would at the same time help solve the housing crisis in American cities. He made some experiments, including a concrete garage on his own estate – a building that still stands – although this was very simple in design and only one-storey.

Edison was granted a patent in 1917 whose introduction reads: “The object of my invention is to construct a building of a cement mixture by a single molding operation, all its parts, including the sides, roofs, partitions, bath tubs, floors etc, being formed of an integral mass …” Such buildings would be insect-proof, fireproof, and easy to clean. The patent goes on to describe how the mould or formwork for a complete house would be made of metal parts bolted together. Concrete would be mixed at ground level and lifted in an endless bucket chain to a funnel at the ridge of the roof, from which it would flow through tubes into the formwork. Metal rods would be positioned in the walls and floors to reinforce the structure. The concrete might be coloured by mixing in pigments. Edison thought the pouring process would take three or four hours. He estimated the cost of a house at $1200. One under construction at Montclair in New Jersey is seen in this picture.

A small number of houses were built here and at Phillipsburg New Jersey, and others for industrial workers in Gary, Indiana, some of which are still lived in today. Edison’s biographers dismiss the venture as a failure, which is true: but it is interesting to ask where the failure lay. From a technical point of view, the process worked, if imperfectly, and those houses that have been looked after are still in good condition. The photo shows the living room of a house in Montclair renovated in 2015: see the concrete stairs and fireplace. Edison even made a groove in the walls at floor level into which the edges of floor coverings could be fitted.

The major problem was the cost and complexity of the metal formwork, which had 2300 pieces plated in nickel to give a smooth finish, and cost $175,000. Edison did not set up a construction business himself: instead he allowed others to exploit the patented method without payment. But this was too big an investment for any small builder. It turned out also that the pouring process had to be carried out not in one operation but in stages. With the time needed for the concrete to set, it took two weeks to complete a house. And strangely, one might think, the idea that these were intended as cheap houses apparently put off buyers. Edison turned his attention to making ‘unbreakable’ furniture from lightweight concrete, including refrigerators, beds and phonograph cabinets. He sent two of these cabinets to be put on show in New Orleans and Chicago, in crates with labels saying “Please drop and abuse this package”. But they never arrived back to a trade fair in New York. This scheme failed too.

But maybe Edison was just too far ahead of his time. A hundred years later, concrete houses are being created with 3D printers - much enlarged versions of the printing devices, driven by computers, which make small models in plastic. For printing at the building scale, a computer-controlled robot squeezes out concrete through a mobile nozzle, like toothpaste from a tube, building up the walls and slabs layer after layer. In 2018 a family in Nantes, France, moved in to what was claimed as the first inhabited 3D-printed concrete house in the world.

US Patent US1219272A, ‘Process of constructing concrete buildings’, filed by Thomas A Edison 1908, granted 1917

Matt Burgermaster, ‘Edison’s ‘single-pour system’: inventing seamless architecture’, paper presented to Society of Architectural Historians 64th conference, New Orleans 2011

Lauren Payne, ‘Concrete Idea: Edison’s Failure Finds New Life’, New Jersey Monthly, November 13th 2015