The black glass skyscraper: a really bad idea

The first large buildings to have walls (and roofs) made completely of glass were the great horticultural greenhouses of the early 19th century. The most magnificent glasshouse of all was of course the gardener Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace of 1851, a conservatory for artefacts collected from across the world. In America at the same time the engineer James Bogardus was pioneering factory and warehouse buildings with iron structural frames and large areas of glazing. Contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic were impressed with how speedily such buildings could be erected from their prefabricated parts.

In 1914 the German novelist and science fiction writer Paul Scheerbart published an odd book predicting a *Glass Architecture *of the future. Not a functionalist but an expressionist, Scheerbart foresaw the aesthetic potential of coloured glass, electric light, glass ornament and glass furniture. He talks about tall glass buildings that will become ‘towers of light’ and will carry searchlights for guiding airships. “Aeronauts will show their indignation at unlit towers.”

Scheerbart is not unaware however of some possible practical drawbacks. He refers to the excessive cost of heating the greenhouses at the Botanical Gardens in Dahlem in winter with coal. (Scheerbart does not mention the Crystal Palace: but that got much too hot in July of 1851, and parts of the vertical glazing had to be removed.) Glass is a material that lets heat pass easily. Houses built of glass will only be suitable for temperate climates, and will need to be double-skinned. Also, it will not be convenient to put furniture against glass walls.

Mies van der Rohe read Glass Architecture. His first major project after the First World War was a competition entry for a tall office building on Friedrichstrasse in Berlin of 1921. Mies’s first idea was that this would be a bare frame structure open to the air. “But”, he said, “if one had to enclose it, all I could think of was to wrap it in glass.” He envisaged storey-high sheets of glass hung off the edges of the floor plates. It was to be ‘an architecture of skin and bones.’ This was the world’s first design for a completely glass-clad high-rise office building. After he moved to the United States, Mies built several such towers sheathed in black or dark glass, the most celebrated being the Seagram Building in New York of 1958.

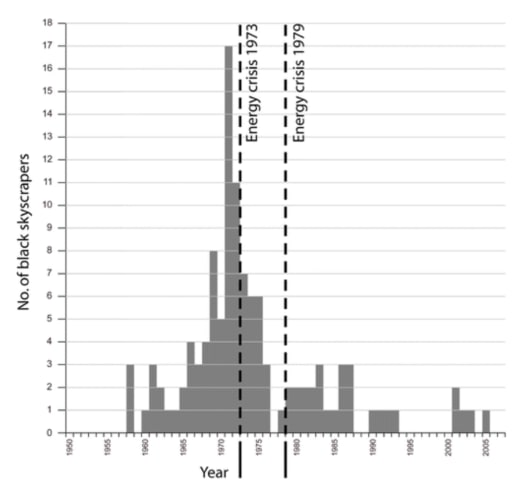

Many architects and developers followed Mies’s lead. The graph above was published by Philip Oldfield and colleagues, and shows the number of black skyscrapers built in selected cities in North America each year since 1950. Notice the peak in 1971, and the sharp drop in numbers following the First Energy Crisis of 1973 when the price of oil quadrupled and gas prices also rose sharply. The construction industry quickly appreciated its serious mistake. Glass buildings lose a lot of heat in cold weather. And black buildings absorb the sun’s heat in summer and need much more cooling.

Despite this salutary lesson however, high-rise buildings continue to be built with glass curtain walls in large numbers today, some of them even black. Why should this be, in our energy-conscious 21st century? One reason, as Bogardus and Paxton showed, is that prefabricated construction can be rapid. The use of glass instead of masonry or concrete panels reduces the loads on the foundations. But glass walls are also thin. Commercial office buildings are valued and rented on the basis of their floor area; and thin walls allow some extra floor area to be sold.

But there is a catch. For her doctoral thesis awarded in 2018, Maria Kikira placed large numbers of temperature sensors in the areas closest to the external perimeters of two office buildings in London with glass curtain walls. The results, and a survey of occupants, showed that these zones adjoining the facades were too cold in winter and too hot in the summer, which – together with blinding glare from the glass – meant that they could not be occupied. The expensive strips of additional office floor were being left empty or used for storage. Paul Scheerbart might have predicted such problems, a hundred years ago.

Paul Scheerbart, Glasarchitektur, Verlag der Sturm, Berlin 1914

Philip Oldfield, Dario Trabucco and Antony Wood, ‘Five energy generations of tall buildings: an historical analysis of energy consumption in high-rise buildings’, *The Journal of Architecture *Vol.14, 2009 pp.591-613

Maria Kikira, Assessing the Environmental Condition in the Zone Adjoining the Façade: A Monitoring Study in Office Buildings, PhD thesis, University College London 2018