Architectural models at a scale of 1:1

Buildings are large and expensive. Many of them are one-offs, and the design is not repeated. Architects have traditionally used physical models of wood or plaster to make predictions, for themselves and clients, of what their schemes will look like once built. Usually these models are reduced in scale, to be of manageable size and relatively cheap to construct (although important sculptural and decorative details may be modelled at actual size). But looking at a scale model is not quite like looking at the completed building, in subtle but significant ways. One tends to view a model from above, as if from a bird’s eye view. It seems like a toy. One cannot get inside it. Architects have used miniature periscopes to experience and photograph their models from the viewpoints of future occupants.

Designers of other costly types of product build models at full size. Car stylists make mock-ups in wood and clay to gauge and adjust the appearance of the bodywork. The cost can be justified if many copies of the identical design are to be manufactured. Even in the construction industry, volume housebuilders will use the first house erected on a site – the show house – as a kind of full-size model to attract purchasers. But for more complex, unique designs of building, the scale model is the norm. With some rare exceptions.

Otto Wagner, one of the leaders of the Vienna Secession movement, had two bays of a projected museum for the city mocked up at full size on site in 1910. It was never built. Hitler’s master architect Albert Speer was influenced by the Secession, and followed Wagner’s example in having several full-size models made of his projected monuments for ‘Germania’, Hitler’s re-planned city of Berlin. These were built by craftsmen from one of Berlin’s film studios in wood and fibrous plaster or ‘staff’, the materials from which the pavilions of the great American international exhibitions had been constructed - the ‘White City’ in Chicago of 1893, and the Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915 in San Francisco.

There is something fitting about Speer as architecture’s Cecil B De Mille and his bombastic oversized classical designs as film sets. Leon Krier in his monograph on Speer’s work says that the purpose of the mock-ups was to test effects of light and shade and try out different surface treatments. But the greater aim was surely to flatter the vanity of the Nazi high command.

A building with distant military associations of a rather different kind was designed by Edwin Lutyens in 1911 as a country house for Julius Drewe, a businessman who made his money in the Home and Colonial chain of grocery stores. Drewe employed a genealogist to trace his family back to the 12th century, to one Drogo de Teynton, who had given his name to the Devon village of Drewsteignton. Drewe acquired land near the village, identified a site on a rocky promontory on the edge of Dartmoor, and commissioned Lutyens to design him a castle such as De Teynton might have lived in.

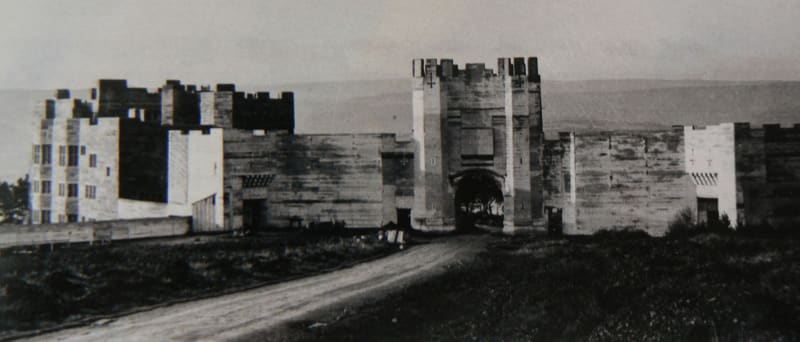

Lutyens’s plan for Castle Drogo was a U-shaped courtyard, to be constructed on Drewe’s insistence in solid granite, six feet thick. Construction proceeded through 1912, but then Drewe panicked at the escalating costs, and ordered that only one wing be completed. In 1913 Lutyens tried to persuade Drewe to build the barbican – a curtain wall and gatehouse – that he had designed to close the court, by constructing a full-size mock-up in wood and canvas to convey the visual effect. Drewe came to inspect the ‘model’ and decided against it. In the end Lutyens resorted to planting thick yew hedges in place of the missing parts of the original scheme.

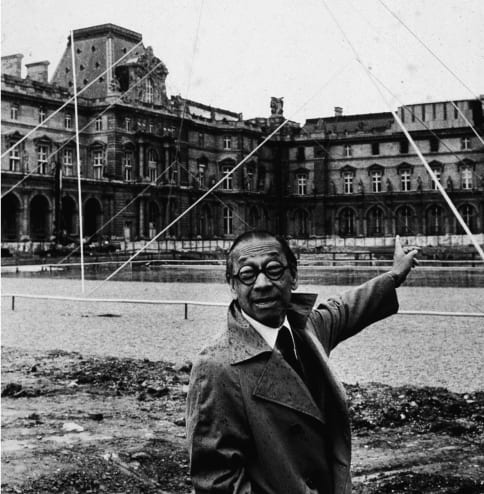

So none of the proposals mocked up by Wagner, Speer or Lutyens was built. On the other hand, I M Pei put up a full-size model of a kind for his controversial glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre. This was nothing more than a thin skeleton made of rods to give an impression of the pyramid’s size . The Mayor of Paris Jacques Chirac came and approved, and the project went ahead.

Today most large architectural schemes are visualised with digital computer models, which are essentially scale-less. Designers and clients can have the impression of moving about inside the models. But the experience is still not quite like being in a real building.

Otto Wagner, exhibition at the Vienna Museum on the 100th anniversary of the architect’s death, 2018

Leon Krier, Albert Speer: Architecture 1932-1942, Monacelli Press, New York 1985

Jane Brown, Lutyens and the Edwardians, Viking London 1996